The absurd power of the archives ran down my native veins, following the trail of oil that led to dreams of home. Growing up in the UK, I remember coming-of-age: returning after A-levels to an unknown letter. Documents granting citizenship. My National Insurance number, the key to taxation. At the time, I used the name Peter, to whom the letter was also addressed. In truth, my first name is Oluwatosin. A fact that later proved detrimental as I spent years untangling government records to correct the name. My full name is Oluwatosin Oluwakayode Ominiyi Temi Tope Peter Adegoke. Yet Peter dominated the first twenty years of my life. Through this experience, I encountered firsthand the absurdity of bureaucracy: the circularity of its logic.

clock in, attempt action, fail, start again, clock in, attempt, enter wrong room, start again, clock in, …

Government ID was essential to access the online portal, a process requiring the generation of a new ID for each session. A system meant to manage taxpayers while preserving freedom. "Stasi or Gestapo officers are a breed apart from the unarmed plod who demands no ID cards from free British people," writes Polly L Toynbee (2025). Now, the Labour government seeks to universalise citizen ID. You could easily lose your Government ID. It was easy to get lost. Kafka's Josef K (1967) faced similar illogic, caught in a bureaucratic maze, filled with "a tundra of pulverizing boredom," as Hitchens (2011) described it. Fisher (2009) relates this to the "crazed Kafkaesque labyrinth of call centers." At the British Museum, an older Black male receptionist barked building regulations, just within his authority: “What does that sign say… exactly. So stand behind the line and wait there. I will call you over when ready.” We all waited anxiously. First our IDs, then proof of address, then a photo, taken by another staff member. The first man saw something in me. We talked about the Docks. He repeated this ritual with another customer—an older Black woman.

My body perched, waiting for the second check. Suddenly, a rustic quake hit my eardrums.

“Oh, are you Nigerian?”

I looked up to see a red-skinned, sunburnt, elongated, navy-seal-blue-suit-wearing, high-cheekboned, combovered, dirty-nailed, shoeshined, old-money meandering mind-body of mass. And his thick, wet posh accent—throbbing down my spine.

“Are you Igbo?”

The final syllable stretched like an elastic sports cap that slowly aches the head but evades detection—forever pervading. He continued,

“My great uncle spoke so highly of the Igbo people.”

I was caught off guard. Like spotting a childhood classmate at church. But I do not know you, Sir. No massa, I do not know yer.

Kafka's influence extends to Orson Welles. In The Trial (1967), characters are dwarfed by vast architecture. My visual language mirrored this with long hallways. At the London Metropolitan Archives (LMA), hallways abound. There, I confronted the Network: materials only viewable with specific authorisation. Use of “Network” aligns with Bruno Latour's Actor-Network Theory: "a network is all boundary without inside or outside" (Latour, 1996). GUI (Graphic User Interface) offer a way to reckon with this concept. It is the paint that fills the gaps on the canvas. Like nodes that extend into a tree of knowledge, composed entirely of connections. Adobe Premiere Pro's layer-based timeline, Da Vinci Resolve’s node-tree structure, and Obsidian’s productivity maps all mirror this theory. At LMA, their Account Management System connected to a legacy system that required in-person visits to Farringdon. Deleuze’s rhizome becomes Latour’s network. These concepts were considered throughout the making of the film. They informed my tools for research allowing my workflow to engage with worlds of knowledge, as opposed to a linear timeline of events.

Time near Balfron Tower, filming for another project, revealed brutalist towers as contemporary castles. Council homes had prestige. Families waited decades. Britain’s welfare state gave birth to these vertical fortresses. Like The Castle by Haneke (1997), where blocking and motion convey Josef K’s existential search, my film was also a search. In creating it, I scripted: “searching for memories of myself” (Artist, 2025). I projected archival objects onto brutalist structures. Collections like the Colonial Film Unit (CFU) are stored across BFI, Bristol Archives, and the Imperial War Museum. Their architecture—brutalist, red-brick industrial, Edwardian baroque—mirrors hegemonic power. See Robert A. Caro (1974), Ismail Kadare (2000-2023), Ken Follett (1989), and Rule of Stone by Danae Elon (2024). Concrete, especially in London social housing, becomes a material metaphor. Architecton by Viktor Kossakovsky (2024) also represents high-rise concrete blocks in Ukraine. My own childhood in social housing became the foundation for connecting personal stories with colonial collections. This creative thread was sewn early.

Mapping this connection led to an investigation into imperialism. The research question evolved into: what role do archives play? In Exterminate All the Brutes (Peck, 2021), a colonial scene is curated by a white photographer. Through this staged image, viewers are encouraged to interrogate the media and its truth claims. Lindqvist (1996) reminds us, “Too many Europeans interpreted military superiority as intellectual and even biological superiority.” Colonial narratives were always epistemological. Donna Haraway’s ‘modest witness’ critiques this blind factualism. The witness becomes “an authorized ventriloquist for the object world” (Haraway, 1997). Her challenge: knowledge must include marginalised voices. The essay film provided such a space. Organisations like TRACTS nurture this kind of experimental research-led cinema.

I began screen recording archives. A low-res necessity due to prohibitive access fees. The Nigerian archivist Didi Cheeka shared his frustrations: Nigeria has struggled to screen CFU content due to licensing costs. This issue intersects with identity. Colonial archives manufactured false meaning through imagery. We must now challenge those meanings through public programming. Fanon writes, “I came into the world imbued with the will to find a meaning in things... and then I found that I was an object among other objects” (1986, 109). Where Darwin theorised man, Fanon theorised the colonial man. His psychoanalytic work revised Jung’s collective unconscious, showing how marginalised groups possess a dual consciousness—Black labour vs. white capital. The archive can destabilise this cultural conditioning.

Foucault calls the archive “the law of what can be said, the system which governs the appearance of statements” (1972, 129). The ancient Greek archive was private, the domain of the arkhē: the first law. Derrida (1996) expands on this in Archive Fever, showing how public access to archives is still mediated by private structures. Hence, “a feeling of getting lost while retracing one’s steps” (Ibid., 72). Like Peck’s photographer, the archive is both record and performance. Latour’s Parliament of Things (2017) argues for negotiation between actors—object and subject—in the knowledge-making process. Derrida’s reading of Freud introduces metaphorical doors: the modalities of archival access. “The three doors of the future to come resemble each other to the point of confusion” (1996, 69). This echoed my own use of tunnels in imagery: the underpassing at Barbican; the bridge Balfron Tower; the hallway Trellick Tower; even the train scene in Giant in the Sun (Samuelson, 1959). These spaces, both public and modernist, carried my story and those of my comrades.

“And more than anything, my body, as well as my soul, do not allow yourself to cross your arms like a sterile spectator...”

Aime Cesaire (1939)

To avoid becoming a sterile spectator is to demand more from both viewer and maker. I struggled to articulate my thoughts. By screening the film to my younger brother’s cohort, I reflected critically. Like Onyeka, I was drawn to dance scenes. “Fundamentally, dance was used in these films to signify what the colonial image considered to be blackness,” says Igwe (2020). But these dances are also acts of resistance, such as during the Aba Women’s Protest. My film began to focus on challenging the colonial image of Blackness. By foregrounding contemporary Black production and framing, I was able to offer a more nuanced representation. My blackness also plays a role here.

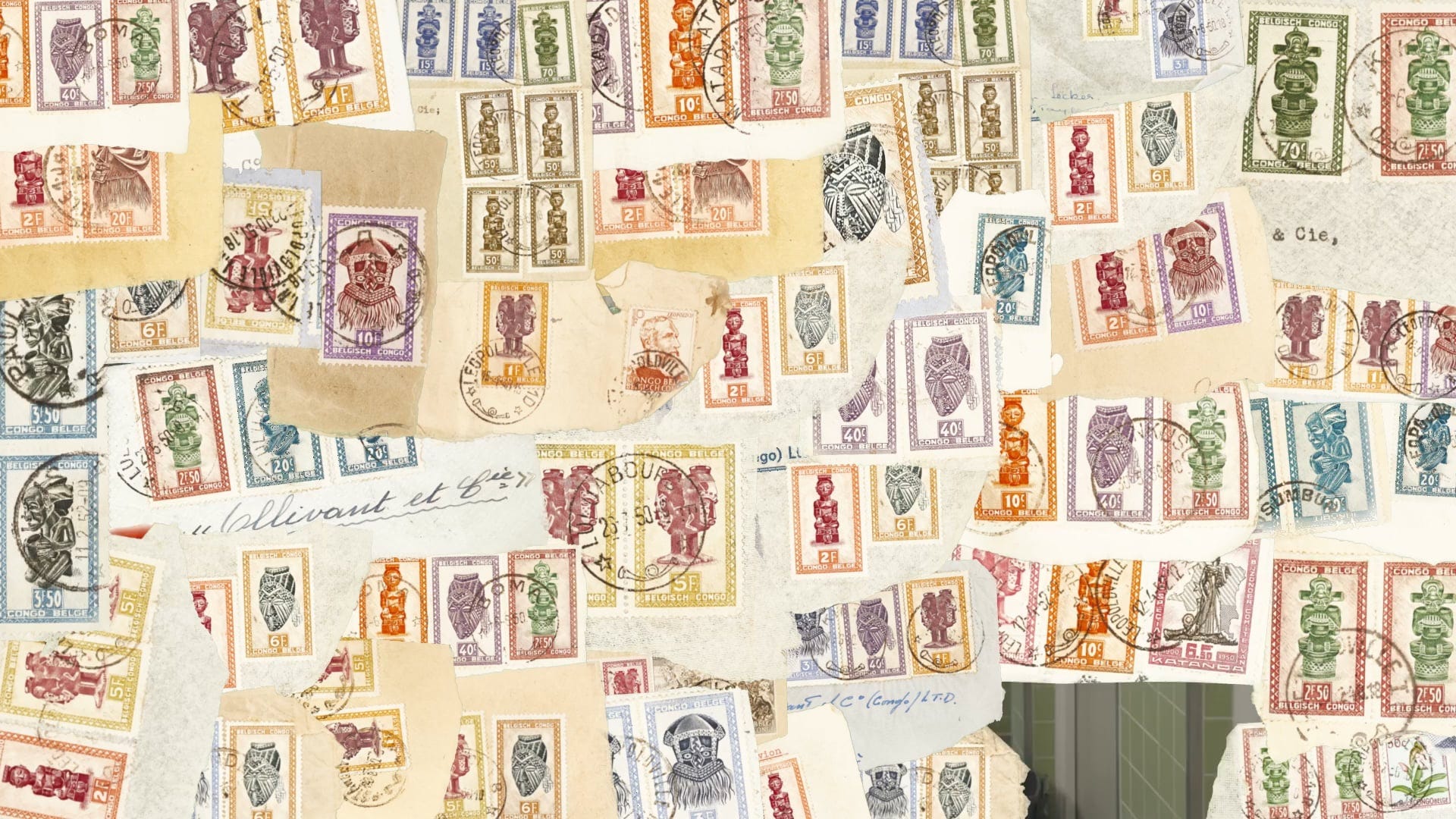

Artists have left us with a legacy of political representation. Ben Enwonwu, a UCL alum, is foremost in mind. While known for painting and sculpture, his work on stamp production deserves attention. In Ghana: The Year of the Quiet Sun (1964-65), stamps became political icons. Enwonwu led a similar effort in Nigeria. By crafting a portrait of the Queen, he hexed her figure. I used stamps to represent nationalism's struggles. After independence, ex-colonies faltered. New forms of colonialism emerged through corporate occupation. Philosophy turned against capitalism, and Third World cinema gained traction. Nationalism became synonymous with post-colonial hope. Didi Cheeka cries, “What happened to the promise of SWAPO?” I think of Ken Saro-Wiwa, Wole Soyinka (1997), resistance embodied. I uncovered a sense of erasure—redacted wars, censored nationalism. I had to include this in the film.

Festac '77 in Lagos was a cultural reset. A pan-African festival celebrating national pride. The festival’s logo, a native mask, was created after the British Museum refused to return the Benin Bronzes. That replica became its symbol. Statues Also Die (1953), Statues Also Die Once Again (2025), and You Hide Me (1970) continue this archival discourse. Decolonising the Archive hosts ongoing conferences on these themes. Esther Stanford-Xosei speaks powerfully on reparations. My commitment preceded this project, but it solidified through the work. I chose Tac One as the typeface—the same as Festac magazine.

The archive is not a passive vessel of memory, but a contested arena of power, identity, and resistance. Through layered reflection, the absurdity of bureaucratic processes, and deeply personal storytelling, I engaged with the archive as both material and metaphor. The film became a medium to explore selfhood through networks of memory, state, colonial history, and digital infrastructure. From Balfron Tower to the British Museum, from Kafka to Fanon, from dance scenes to digital nodes, this project stitched together the fragmented echoes of a colonial past to form a coherent yet questioning present. Representation is not enough; transformation is required. In pushing through the tunnels of archives, I did not merely revisit the past—I reassembled it, forming a new structure through which identity might emerge.

Works Cited

Adegoke, Oluwatosin, director. Archives Also Die. Goke Studio, 2025.

Caro, Robert A. The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. Bodley Head, 2019.

Césaire, Aimé. Notebook of a Return to My Native Land: Cahier D'un Retour Au Pays Natal. Edited by Annie Pritchard, translated by Mireille Rosello and Annie Pritchard, Bloodaxe Books, 2020.

Derrida, Jacques. Archive fever : a Freudian impression. University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Elon, Danae, director. Rule of Stone. Danae Elon and Paul Cadieux, 2024.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. Translated by Richard Philcox, Penguin Books, Limited, 2021.

Fisher, Mark. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Zero Books, 2009.

Follett, Ken. Die Säulen der Erde. HarperCollins, 1989.

Foucault, Michel. L'archéologie du savoir. Gallimard, 1969.

Haneke, Michael, director. The Castle. Veit Heiduschka, Christina Undritz, 1997.

Haraway, Donna Jeanne. Modest−Witness@Second−Millennium.FemaleMan−Meets−OncoMouse: Feminism and Technoscience. Routledge, 1997.

Hayden, Lucy K. “‘THE MAN DIED’, PRISON NOTES OF WOLE SOYINKA: A RECORDER AND VISIONARY.” CLA Journal, vol. 18, no. 4, 1975, pp. 542-52. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44329184. Accessed 12 6 2025.

Hitchens, Christopher. Hitch-22: A Memoir. Grand Central Publishing, 2011.

Igwe, Onyeka. “being close to, with or amongst.” Feminist Review, vol. 125, no. 1, 2020, pp. 44-53. Sage Journals, https://doi.org/10.1177/0141778920918152. Accessed 12 6 2025.

Julien, Isaac. Once Again... (Statues Never Die). 2022.

Kafka, Frank. The Trial. Verlag Die Schmiede, 1925.

Kossakovsky, Viktor, director. Architecton. Ma.ja.de., 2024.

Latour, Bruno. On actor-network theory: A few clarifications. Soziale Welt ed., vol. vol. 47, Nomos, 1996. no. 4 vols. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40878163.

Lindqvist, Sven. Exterminate All the Brutes. Translated by Joan Tate, New Press, 1996.

O’Donoghue, Darragh. “Review of Exterminate All the Brutes.” Cinéaste, vol. 47, no. 1, 2021, pp. 44-46. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27087984. Accessed 12 June 2025.

Owoo, Nii Kwate, director. You Hide Me. 1970.

Peck, Raoul, director. Exterminate All the Brutes. Daniel Delume, Sara Rodriguez, 2021.

Proust, Marcel. In Search of Lost Time [volumes 1 to 7]. Pandora's Box, 2024.

Resnais, Alain, et al., directors. Les statues meurent aussi [Statues Also Die]. Présence Africaine, 1953.

Samuelson, Sydney W. W., director. Giant in the Sun. Nigerian Film Unit, 1959.

Simons, Massimiliano. “The Parliament of Things and the Anthropocene: How to Listen to ‘Quasi-Objects.’” Techné: Research in Philosophy and Technology, vol. 21, no. 2/3, 2017, pp. 150-174. Philosophy Documentation Center, https://doi.org/10.5840/techne201752464. Accessed 12 6 2025.

Toynbee, Polly. “ID cards could work for Britain - and in the fight against reform.” The Guardian [London], no. Journal, 10 June 2025.

Welles, Orson, director. The Trial. Film Finances, 1967.